Before she was even out of high school, Killeen resident, Miranda Castro, 24, acquired the kind of wisdom that no one welcomes. Not the gentle kind that sprouts after seeds of age, experience, faith, and fate are watered with time and the sunlight of understanding. It is the kind of experience wrought from hardship and loss.

Before she was even out of high school, Killeen resident, Miranda Castro, 24, acquired the kind of wisdom that no one welcomes. Not the gentle kind that sprouts after seeds of age, experience, faith, and fate are watered with time and the sunlight of understanding. It is the kind of experience wrought from hardship and loss.

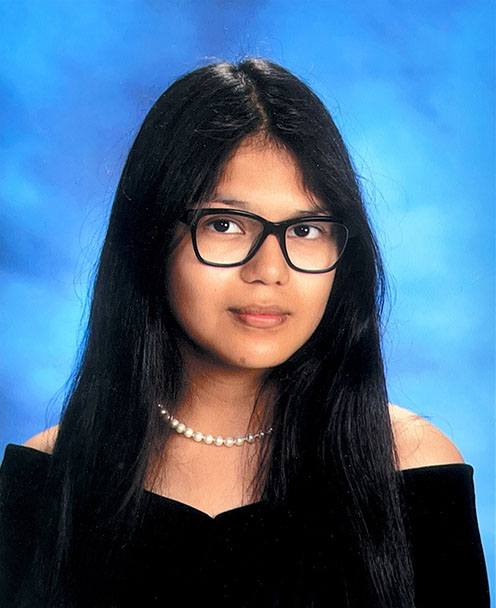

Castro, a student at Texas A&M University–Central Texas, is entirely composed as she tells her story, abstractly folding and re-folding a Kleenex in her hands as she speaks. Her thick dark brown hair falls forward over her shoulders and down her back, and the no-nonsense rectangular eyeglasses partially obscure her deep brown eyes until she pauses to look up and speak.

At one time, she was one of hundreds of other juniors at Ellison High School. She played the flute in the marching band and took audio visual classes at the Career Center that would lead to a job as a camera operator for KISD television. She held A’s and B’s – and a few C’s, she says, if the subject of the class was super hard.

Miranda’s mother, Margarita, praised her daughter’s academic interests, including her natural talent for math and science, but because good moms know these things, she also loved to see her celebrate the kind of high school traditions that made special memories – like having a giant mum to wear during homecoming.

“She went all out in my junior year and made this super-sized mum,” Castro said, smiling as she shared a photograph of the once brilliant green and white Ellison colors – now faded, but no less precious. Its ribbons, she noted, were long enough to reach from her shoulder to her shins. And, because nothing is too big in Texas, a six-inch stuffed eagle had been added, still nesting deliberately in the very center of a ginormous white mum.

“I love that she made it with her own hands, and that she put so much of herself into it,” Castro said. “I wore it as a junior – and as a senior – even though it had faded. It is just one of those things that was made with love.”

Daughters know these things. The lucky ones know. Mothers make their wishes for their children known. But when wishes are insufficient, they act. They build a foundation of love for them and nudge them along in the right direction, sometimes wanting more for them than they had for themselves.

“When my mother was younger, she wanted to be a lawyer,” Castro said. “She took classes, but back then – when we were small – there were no options other than physically going to class and having three small children eventually made it too hard. She regretted that, but it didn’t make her bitter. It made her want more for us.”

Her mother, she says, missed no opportunity to remind her daughter that there was no such thing as not going to college. And older sister had already moved out and begun her undergraduate degree at Texas State University.

Next in line, Miranda knew her time was coming. She was a senior, and not only did she know what she’d be doing after high school, she knew why. Her mother, Margarita, had provided those answers: She wanted for her daughters not just the degree, but the future the degree made possible: Careers. Security. Stability. Fulfillment.

After hearing and taking to heart her mother’s exhortations, there was no doubt in Miranda’s mind that college was a certainty in her future – until the day she knew it wasn’t. At least not the way her mother had wanted it to be. The day her carefree high school days changed. As did she.

Halfway through her last year of high school, Castro learned that her mother had been diagnosed with stage four cancer. Treatment – then local – began immediately. With her older sister away at university, she instinctively took the lead.

“It became all about family,” she said, without a hint of regret for all that the diagnosis meant to what had been her plans for college. “My older sister wanted to leave college and come home, and my mother wouldn’t hear of it. And my younger sister was a junior in high school. We had to be brave and keep living our lives because that’s the only way my mom would have it.”

At first, her mother’s treatments were in Harker Heights, she said. But very quickly, as her condition worsened and the cancer advanced to other parts of her body, her care required expertise that was only available in Round Rock.

At first, it was an obstacle – for the simplest and most taxing reason: Castro had her driver’s license but had yet to drive on interstate highways. Seems trivial in retrospect, she admitted, especially given the much larger responsibilities she was taking on, but the thought of it terrified her.

Who knows the source from which more courage comes when a girl her age takes on large scale adult responsibilities one after another, voluntarily surrendering what she had thought was her future, only to be confronted with one more thing. Trivial to some people, she knew. But nonetheless. Still. One more thing.

Time passed. She was her mother’s caretaker. Her little sister’s stand-in mom. And all she could do was watch as her circle of friends readied themselves for college in the fall. But never then, nor to this day, did she regret that she wasn’t doing the same.

“My mother would always apologize to me, telling me that she was sorry that I was putting off college to take care of her,” she confessed, her voice quivering slightly. “I would tell her that it was okay and remind her that college wasn’t going anywhere any time soon. I wanted to be sure that she knew that I wanted to be there for her.”

For three years, she said, she was at her mother’s side: at the hospital for treatment, at the doctor’s office, and at home where she would eventually enter into hospice care. Never once did she mark the time by remembering what she might be missing out on.

Perhaps it was a mother’s prayers that worked a miracle. Perhaps it was the bonds of true friendship. Perhaps fate was just doing what fate does.

She had stayed in touch with her good friend, Miranda Mercado-Batista, after high school. Mercado knew of her friend’s mother’s illness and how much her friend had wanted to begin college. But because they had stayed in close contact with each other, she also knew that her friend was deferring college – or perhaps not going at all – and that is when she intervened. An act of kindness that Castro says she will never forget.

“When my friend heard about my plans not to go to college after all, she was already in her first semester at Austin Community College,” she explained. “She had enough to do that semester, and she could have just focused on herself, but she didn’t.”

Her friend, she said, knew that her mother’s treatment was at a hospital in Round Rock, and she also knew that the ACC-Round Rock campus was literally right around the corner from that facility.

“Because of her, I didn’t waste any more time,” Castro explained, adding that she enrolled the following Spring 2019, while still helping my mom out. She owes a lot to her friend, she adds.

“Without her help, I think it’s possible that I would have not gone at all or that it might have been years before I did,” she admitted.

That spring, Castro began classes, at first majoring in computer science. An out of district student, her tuition was more than the affordable rate offered to in-district students. Still. She persisted, paying her own tuition with the income she earned from a camera operating job that she had wedged into her already packed schedule.

Any college student will attest that a full schedule of courses is nothing to take lightly. Neither was the full schedule of computer science classes. There were 2 a.m. nights and 6 a.m. alarms. And there she was, she thought: In the same shoes her mother had been in when she had enrolled in college herself all those years ago.

Something rose up in her. Not as immediate or unruly as defiance but rise within her it most certainly did. She switched to computer information systems, earning her an earlier graduation date. More than anything, she wanted her mother to see her cross the stage. As ill as she had become, she encouraged her daughter, urging her on. Reminding her not to quit. Keep going, she told her.

Maybe her mother knew. She had battled for almost five years to live. Bravely remained present for her daughters and her family. A hospice bed was brought into the living room. That memory, Castro stoically added, is where she saw her mother for the last time. And when the hospice bed was taken away, she spent a year sleeping as near to the last place her mother had been before she died – the sofa – because, she said, it is where she felt closest to her.

In those long days and weeks and months, anyone else might have surrendered to the loss, put aside finishing the semester she had started, and just allowed themselves to let the grief swallow whatever goals she had set – even when they were but one semester away from completion.

This mother’s daughter did not give up. In Spring 2022, she graduated from Austin Community College only a smidge of a decimal point -- .047 -- away from honors.

Funny how the themes that are sometimes like guideposts when the way forward might have been otherwise obscured. Friends – the good and genuine kind – were crucial to Castro’s degree achievement. And so, it would be so again.

Monique Bullock and she had attended the high school’s career center together but hadn’t met. They had attended a conference in Dallas and Bullock was the first to say hi when they reunited on the A&M-Central Texas campus on Castro’s first day of classes.

Now colleagues in student government, Castro is grateful for her friend’s encouragement, noting that Bullock never hesitates to push her for greater things. If she has anything to say about it, Castro laughs, her friend won’t rest until Castro, too, is pursuing her graduate degree.

Castro would be the last person to brag about such things, but the end of her first semester was punctuated with a nice shiny 4.0. This May, she receives her undergraduate degree. No doubt, with her mother’s blessings.